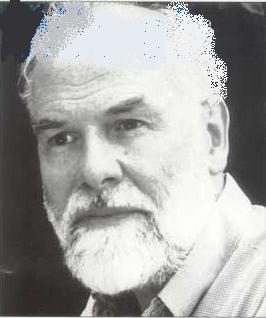

Peter Winch

Lecturer in Philosophy, Swansea University Professor of Philosophy, Kings College London

Peter Guy Winch was born in London in 1926 and went on to enlist in the Royal Naval forces where he served during the second World War. When the war ended Winch decided to take an academic route, studying Philosophy, Politics and Economics at Oxford University—completing his degree in 1949. After this he obtained his BPhil in 1951 under the guidance of the eminent Oxford philosopher Gilbert Ryle. In that same year, Winch secured a post as lecturer at University College, Swansea, remaining in that position until 1964. Over that period he maintained a strong academic association with colleague Rush Rhees, a close friend of Wittgenstein. Winch later credited Rhees with fruitfully directing him in many of the fundamental questions of philosophy. Under the influence of Rhees, Winch also became an important translator and interpreter of Wittgenstein' s writings and would eventually become one of the trustees of Wittgenstein’s unpublished papers, devoting considerable effort to the Nachlass and collaborating with D. Z. Phillips on volumes in honour of Rhees. He also distinguished himself as a translator, notably of Wittgenstein’s Culture and Value, refining the English text of that often challenging set of remarks.

At Swansea, Winch wrote the seminal work, The Idea of a Social Science in which he warns against social science’s tendency to reduce human behaviour to mere causal laws, arguing instead for attention to nuanced, moral-laden “thick concepts.” Winch views the expressive qualities of language as integral, not incidental, to objective understanding, and in this respect abstract theories should stay accountable to everyday discourse or risk distorting social reality. In the book he emphasises that meaning emerges only within communal rule-following practices, rejecting any purely private or mechanistic model. Winch critically insists that reflecting on reasons and justifications is categorically different from identifying physical causes, so human action cannot be explained in the same way as inert phenomena. This leads to a critique of imitating natural science methods in the analysis of social life, which requires an interpretive framework that recognizes historical and cultural contexts. Against views that philosophy merely clears confusion, Winch reaffirms its constructive role in clarifying conditions of intelligibility. The Idea of a Social Science continues to attract readers from philosophy, sociology, and anthropology, drawn by its bold insistence that meaningful analysis demands a careful examination of what people actually do in daily living in the context of the conceptual schemes guiding their actions, rather than merely applying external scientific criteria. This outlook underwent additional refinement in the influential paper Understanding a Primitive Society, where Winch urged investigators to avoid haughty misinterpretations of unfamiliar cultures by attentively noting the distinctive settings in which spiritual or ceremonial customs occur. His position incited controversy: certain social researchers deemed his method excessively contextual, while others regarded it as a crucial corrective to scientistic generalisations about human practices.

During the middle part of the 1960s, Winch relocated to London. He began as a Reader at Birkbeck College and, starting in 1976, assumed the Chair of Philosophy at King’s College. His endeavours in that role reinforced his standing as a stringent, perceptive thinker. Winch cultivated close ties with Norman Malcolm and Raimond Gaita, treasuring Malcolm’s “patient honesty,” an attribute he deemed vital to authentic philosophical lucidity. While teaching at King’s, Winch upheld his exacting pedagogical style. He insisted that students exercise independent thought rather than simply embracing favoured doctrines. This attitude reflected his belief that discussion, rather than class instruction, as the most valuable path to philosophical clarity; a perspective shared by Rush Rhees.

Winch’s published output included numerous essays and further book-length studies. Among these were two collections, Ethics and Action (1975) and Trying to Make Sense (1987), in which he deplored the distortions he believed generalizations frequently produce in moral philosophy. Instead, he championed attention to how moral concepts gain meaning within particular everyday forms of life. This orientation, heavily influenced by Wittgenstein, included a marked appreciation of ordinary surroundings, which he saw as threatened by metaphysical overreach or reductive theorising. His intellectual honesty and willingness to confront unexamined assumptions ran throughout his work and though his challenges often went unanswered by mainstream philosophers, they amounted to a robust critique of prevailing trends.

Winch’s involvement with the philosophical community was also extensive. From 1965 to 1971 he served as editor of Analysis, at that time one of the foremost journals in analytic philosophy. In 1980–81, he presided over the Aristotelian Society, a testament to the high regard in which he was held in Britain. In 1995–96 Winch served as President of the American Philosophical Association’s Central Division. Lecturing widely across Europe and the United States, Winch forged connections with philosophers from many different backgrounds. During this period he explored the writings of the French philosopher, mystic and political thinker Simone Weil. The resulting book, Simone Weil: The Just Balance (1989) identified parallels between many of Wittgenstein’s philosophical themes and Weil’s spiritual and moral reflections. Although Winch claimed that philosophy itself should not dictate which moral or religious views are correct, he noted that Weil’s writing—on factory oppression, political legitimacy, the difference between duty and love, and the role of grace—often compels a moral stance once we truly see what she points out. Winch draws attention to Weil’s emphasis on “hesitation before others," which captures a basic human response that serves as a protective from treating people as mere objects, grounding concepts of personhood and justice in immediate, unreflective reactions. For Weil, knowledge and morality both emerge in a dynamic of recognition, where one must give honest attention to what exists rather than imposing one’s will on reality. Winch found this idea closely linked to Weil’s religious meditations, particularly her insistence that the “spiritual” can be discerned only in the physical fabric of life, illuminated by the right kind of attentive openness. Winch believed Weil’s writing exemplified the power of “reminders” that transform how we see our world. While he remained careful not to become an advocate of her religious doctrine, he acknowledged that her reflections push philosophy across its conventional boundaries, prompting us to confront, rather than merely conceptualize, the moral and spiritual dimensions of human existence.

In 1984 Winch accepted a senior appointment at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. He taught there for a dozen years, a period many of his colleagues saw as exceptionally productive. Winch engendered stability at the department as a figure of intellectual authority, supporting younger scholars and fostering a wide international network of philosophers. In 1995 Winch as among those who organized a conference on Wittgenstein in America, which emphasised his ongoing commitment to furthering conversation on Wittgenstein’s Nachlass. Because he belonged to multiple circles—Swansea, King’s, Urbana-Champaign—Winch had a wide impact, shaping approaches to the philosophy of social sciences, ethics, and religion.

As a trustee of Wittgenstein’s Nachlass, Winch worked to preserve an intricate body of unpublished writings and to ensure that future scholars could study them fruitfully. His translations demonstrated a precise sensitivity to Wittgenstein’s nuanced remarks, reflecting his broader commitment to serious textual scrutiny. Students, too, recall how he insisted that philosophical questions were not narrow academic exercises but an essential undertaking for anyone trying to achieve clarity in their thinking about human life. Some recalled how Winch often grounded discussion in specifics, sometimes signalling his disapproval by grinding his teeth when someone ventured a hasty or muddled claim. Winch saw moral and social issues as inseparable from the ways language is used to frame them; for him, philosophical progress came through careful attention to those contexts and a willingness to question one’s own presuppositions.

Even outside the strictly professional sphere, Winch’s intellectual passion was evident. He had a deep love for music, especially opera, which he felt could illuminate dimensions of experience that might otherwise be overlooked in purely discursive analysis. He was at work on a study of Lessing’s discussion of the Resurrection and on a book about authority when he died suddenly in 1997 after returning from an APA meeting. In reflecting on Winch’s loss, colleagues cited the generosity of his spirit, his integrity, and his refusal to compromise on philosophical seriousness.

Winch left behind a legacy of scholarship that ranges from philosophical analyses of social sciences to further investigations of ethics, religion, and cultural life. Throughout that scholarship runs a shared thread: the conviction that philosophy must not shy away from everyday reality if it is to illuminate how people actually live and think. In his teaching and writing, Winch reasserted the value of detailed, uncompromising scrutiny of concepts as they appear in ordinary settings. Doing so, he believed, opens a path to understanding how the world is ordered through mutual intelligibility rather than through abstract theorising. The influence of Peter Winch endures for those who find in a Wittgensteinian approach a corrective to overreaching systematic philosophies and for those who suspect that contemporary perspectives on ethics or the social sciences sometimes obscure more than they clarify.

Recommended further reading:

Peter Winch by Colin Lyas (1999)

“This is the first introduction to the ideas of the British philosopher, Peter Winch (1926-97). Although author of the hugely influential "The Idea of a Social Science" (1958) much of Winch's other work has been neglected as philosophical fashions have changed. Recently, however, philosophers are again seeing the importance of Winch's ideas and their relevance to current philosophical concerns. In charting the development of Winch's ideas, Lyas engages with many of the major preoccupations of philosophy of the past forty years. The range of Winch's ideas becomes apparent and his importance clearly underlined. Lyas offers more than an assessment of the work of one man: it introduces in a sympathetic and judicious way a powerful representative of an important and demanding conception of philosophy.”

Value and Understanding: Essays for Peter Winch by Raimond Gaita

“The voices in this volume, those of philosophers from Britain, Europe, America and Australia, speak in different tones of sympathy and criticism of Winch and his conception of human conditioning.”

Sense and Reality: Essays out of Swansea (2009) John Edelman (ed.)

“This book is a collection of essays each of which discusses the work of one of eight individuals - Rush Rhees, Peter Winch, R. F. Holland, J. R. Jones, H. O. Mounce, D. Z. Phillips, Ilham Dilman and R.W. Beardsmore - who taught philosophy at the University of Wales, Swansea, for some time from the 1950s through to the 1990s and so contributed to what in some circles came to be known as 'the Swansea School'. These eight essays are in turn followed by a ninth that, drawing on the previous eight, offers something of a critical overview of philosophy at Swansea during that same period. The essays are not primarily historical in character. Instead they aim at both the critical assessment and the continuation of the sort of philosophical work that during those years came to be especially associated with philosophy at Swansea, work that is deeply indebted to the philosophy of Ludwig Wittgenstein but also distinctively sensitive to the relevance of literary works to philosophical reflection.”

Books by Winch:

The Idea of a Social Science and its Relation to Philosophy (1958)

Ethics And Action, (1972)

Simone Weil, the Just Balance (1989)

Trying to Make Sense (1987)

Disclaimer: this website is for general information purposes only and is not directly affiliated to Swansea University or any author mentioned herein. Synoptic overviews by Ben Bousquet (Swansea). Any comments, corrections or queries are welcome and can be directed here: ben@theswanseaschool.org

We need your consent to load the translations

We use a third-party service to translate the website content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details in the privacy policy and accept the service to view the translations.